Experiencing Soweto and the Real South Africa

.

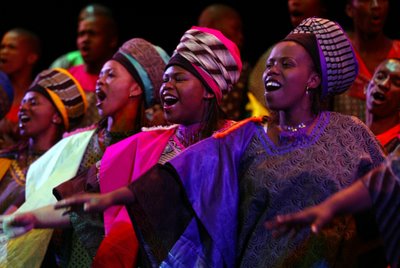

The Soweto Gospel Choir in a live stage performance.

This month marks the 30th anniversary of the June 16, 1976 Soweto riots that led to a nationwide resistance movement that eventually culminated in the unbanning of Black political parties and the release of Nelson Mandela from prison. There's a lot more to Soweto than meets the eye. Africa's most famous community is colorful, sophisticated, vibrant and full of joy. With a little bit of extra effort and some help from the right Black tour companies, you can transcend the surface level and get more into the real groove of the people and their lifestyle. Soweto is a great community to visit, and there are many ways to experience its unique African urban culture and sense of unity and oneness.

Experiencing Soweto and the Real South Africa

Most Americans have heard of Soweto, and the sprawling, unruly South African township conjures many images to mind, although most of them are confusing, limited or inaccurate, or at least only partial pictures of the beautiful whole. Soweto itself is more of a reflection of the many contradictions and paradoxes of South Africa. It is a ghetto, to be sure, but Soweto is also a place of aspiration and wonder, a place of leaders and entrepreneurs, a place rich with its own history, languages, music and vibrancy. When you’ve tasted Soweto’s restaurants and friendly shebeen ‘juke joints’, its crowded streets and playful markets, its love, laughter and hospitality, then you understand why a favorite bumper sticker reads, “To live and die in Soweto.”

What is often confusing for visitors is that Soweto – an acronym for South Western Townships – is actually a vast grouping of neighborhoods and townships of 3.5 million people that is larger than the city of Johannesburg itself. Soweto’s first township, Klipspruit, was formed in 1904 to provide African workers for the mining industry and menial laborers for white Johannesburg; since then Soweto has exploded into an expanse covering some 200 square kilometers of seemingly unending dirt roads, tiny homes and makeshift shacks. As Johannesburg grew, more and more people from rural homelands swarmed into the city looking for work, and Soweto in turn became more crowded, drawing the countless masses to its bosom like a compassionate mother who always manages to take in more orphans.

Africa’s most famous community is more than just an apparition of apartheid – it is home to some of South Africa’s most influential media personalities, writers, actors, musicians, celebrities, athletes and professionals. Soweto has its shanties and informal settlements, as well as its own mansions, model homes and middle class communities. Many of South Africa’s high profile national politicians and business leaders still can be found in Soweto during the weekends or when Parliament is not in session – even though they own expensive homes in the exclusive suburbs of Johannesburg, Durban, Pretoria and Cape Town.

This June – without much international notice or fanfare – marks the 30th anniversary of one of South Africa’s most important holidays, a source of great pride for Sowetans. It can be argued that on June 16, 1976, the new South Africa was born, with the violent riots that broke out after Soweto school children protested against changing the language of instruction from English to Afrikaans. The young Sowetans knew the implications; studying in Afrikaans – a modified form of Dutch – would isolate them further from the mainstream economy and the rest of the world, and make them even more subservient to the Dutch descendent white Afrikaners, the creators of apartheid. The frustration with apartheid’s uncompromising segregation in housing, jobs and virtually every aspect of life had been building up – like a pressure cooker – and the Afrikaans policy was the final straw that broke the camel’s back.

On an otherwise quiet, overcast June afternoon, the young Sowetans took everyone – and perhaps even themselves – by surprise. They agreed to walk out of their classrooms and meet at Orlando West Secondary School on Vilikazi Street, and then march from there to Orlando Stadium. By mid-morning thousands of students had gathered at Orlando West, streaming in from all over the township, until more than 15,000 uniformed students, ranging in age from about 10 to 20, joined the march. But along the way to the stadium the young protestors were met by a phalange of policemen who ordered them to disperse. When the students refused and began singing the spiritual anthem “Nkosi Sikeleli” (God Bless Africa), the police fired teargas canisters into the crowd; the students were unwilling to retreat, and some responded by throwing rocks and bottles. Police then fired indiscriminately, and children began to drop. Although the official estimate is that 23 students were killed, it is well known that in Soweto, everything and everyone is undercounted; other sources indicate that some 200 children were killed, not to mention those who were injured or crippled as a result of the police action.

A photographer for The World newspaper, Sam Nzima, witnessed the riots and snapped the now iconic image of 12 year-old Hector Pieterson being carried in the arms of Mbuyisa Mkhubo, running alongside Hector’s sister, Antoinette Sithole, from the scene. The haunting photograph was carried on news wires around the world and portrayed the brutality of apartheid repression in stark, terrible terms. As the first youth to die in the riots, Hector Pieterson became a symbol of the defiance and restlessness of South Africa’s younger generations, yearning for change. Later that night, as Soweto went up in flames, the rioting spread to the Black township of Alexandra, and then throughout all South Africa. It was as if Pieterson’s death was a unanimous signal that flashed across the nation, saying the time of waiting is no more.

The Soweto uprising set the government at loggerheads with Black urban communities in what would become a non-stop civil disobedience movement that finally culminated with the release of Nelson Mandela from prison and the unbanning of Black political parties like the African National Congress (ANC). Many of the youth involved in the Soweto conflict chose to leave the country, going into exile to join the armed resistance. The “Soweto Detachment,” as they became known, bolstered the ranks of various liberation armies that at times infiltrated South Africa and sabotaged government or military facilities. Other Soweto cadres were fortunate enough to be given scholarships and opportunities to earn college degrees in Europe, the United States and the Soviet Union.

Even before the ’76 Soweto riots, another popular movement based in Soweto had a different, yet in some ways more formative role in the prolonged struggle against apartheid. During the 1950s Defiance Campaign – when a fiery, young Nelson Mandela led people of all racial groups in a series of boycotts, strikes and civil disobedience – another birth of sorts took place in Soweto. On June 6, 1955, more than 3,000 delegates of resistance organizations, of every race and ethnicity, made with their way to Kliptown to approve The Freedom Charter, a declaration of human rights that became part of the foundation of South Africa’s 1996 Constitution. In the middle of one of the poorest sections of Soweto, the representatives gathered on the parched, crowded, dusty land and agreed upon an eloquent statement of their ideals, a dream that would only be fulfilled decades later.

Kliptown today is being transformed through an ambitious redevelopment project that includes the Walter Sisulu Square of Dedication – a memorial on the original Freedom Square site – along with a housing development, a shopping mall and a luxury 4-star hotel. The Square and the entire site are built on a new cosmopolitan vision of Soweto, and are adjacent to some of the most colorful and thriving street markets in the township. Yet Kliptown is also home to one of the poorest squatter camps in Soweto. The contrast typifies Soweto – a modern urban world of information and a hip, multi-cultural African personality, with new aspirations – and a village community that is not far removed from the earthly humanity of traditional Africa. This fascinating contrast seemingly keeps drawing the CEOs and the CFOs, the marketing directors, the Members of Parliament, celebrities, entrepreneurs and musicians back to Soweto.

As South Africa opened to democracy and the international community, a new generation of Black Soweto tour operators created new opportunities for travelers and visitors to experience the energy, joy and beauty of Soweto. Despite its history as a “location” preserve for Africans, a region walled in from white Johannesburg – Soweto is more accessible and welcoming to foreigners, visitors and tourists than one might think. Typically tourists interested in Soweto take a standard bus tour to the Hector Pieterson Memorial, perhaps with a visit to the old homes of Nelson and Winnie Mandela, and Desmond Tutu. Yet these tours only skim the surface and leave visitors with a very superficial contact and understanding of Soweto. Some Black-owned tour companies like Jimmy’s Face to Face and Imbizo Tours take tourists directly into the homes and communities of Sowetans, with surprising results.

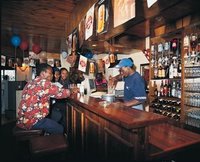

Mandy Mankazana, who started her Imbizo Tours business in 1994, offers tourists the opportunity to live with a Soweto family, to experience their community and township life firsthand, in more intimate person-to-person encounters. “Imbizo” – which means a cultural or community gathering in Zulu – offers a wide variety of “township” tours, including a night-time “shebeen crawl,” which takes visitors on an adventurous party through many of Soweto’s famous home pubs, where Black South Africans love to socialize. But the most rewarding and powerful of her tourist experiences are the live-in visits with Soweto families.

“I propose to the client if they want to stay with a poor, middle class or rich family,” Mankazana explains, pointing out that she allows each tourist to determine the kind of family experience they would like to have. She says she gets “a lot of requests” for the live-in experience – from both Black and White clients – as most of her business comes from word of mouth, personal referrals and the Internet. “For the tourists it is a lifetime experience. When they come back from South Africa they’ve had a lifetime experience. They’re not treated like tourists – they’re accepted like a family member and they feel like they are a part of the family.”

Mankazana says that tourists have many misconceptions about Soweto, but once they experience her tours they always feel safer in Soweto than they do in downtown Johannesburg. Invariably they have great experiences in Soweto, whether they are Black or White, even though tourists usually have stereotyped views of the residents and how they might be accepted in Soweto. Mankazana feels that the tourism sector in Soweto is underdeveloped, and certain factors contribute to confusion about what Soweto has to offer and the kind of tours that are available to visitors.

“I don’t think the tourism sector is really opening up to Bed and Breakfasts in Soweto. They could do more business; they’re not as busy as hotels in Jo-burg,” Mankazana says. She also feels that some White tour operators have set up tours that take people to the Hector Pieterson Memorial and rush them through Soweto, without having contact with ordinary Sowetans, or allowing tourists to patronize Soweto’s curio shops, restaurants, arts and crafts stores, etc. She hopes that more tourists – particularly African Americans – will research the tour operators carefully to find a Black company that will offer more in-depth experiences in Soweto.

Angelia McGowan, a public relations contractor with the Colorado Department of Transportation, recently returned from a 10-day trip to South Africa where she tried the Imbizo live-in experience in Soweto and “shebeen crawl” before she went to an international conference on traffic safety in Durban. McGowan, 33, was overwhelmed by the friendliness and hospitality of Sowetans, and Black South Africans generally. She stayed with her host, Jane Oarabile-Monakwane, in a one-room Soweto dwelling that was in the backyard of a larger home. McGowan said her host’s room – one of three rooms in the same backyard, all with plastered walls and ceilings – was “set up nice, like a dorm room in a college, with a wardrobe” and had a TV along as well as a computer with an Internet connection.

“Everyone in South Africa was very open – more open than I expected for me being a foreigner there. If I didn’t open my mouth I felt like I fit in, but as soon as I opened my mouth I felt like a foreigner,” McGowan said. She said that Sowetans usually greeted her in Zulu or Sotho, but quickly switched to English once they heard her African-American accent. “As soon as I opened my mouth they knew I came from somewhere else.”

During the shebeen crawl, McGowan found that Sowetans were eager to talk to her about living conditions in the United States, and subjects like the recent Hurricane Katrina disaster. Sowetans were quick to open up to her, with a sense of love and community that seems to be an inherent part of African culture. At the shebeens she met lawyers and doctors, and people in the entertainment industry, along with ordinary Sowetans, all in the same setting. Some of the Sowetans she met invited her to stay with them during future visits to South Africa.

“Everyone was so open, I couldn’t believe that people would tell me the next time I come I could stay with them. This was only after five minutes of talking,” McGowan explained, saying she was taken back by the kindness and authenticity of the Sowetans. “It wasn’t a pickup line. They were just being very genuine. They are always open to visitors. They take great pride in hosting and entertaining visitors.”

Through Imbizo Tours, McGowan was also able to arrange to stay with a Black South African host in Durban, the site of the international road safety conference. Her host, Fikile Molefe, also accompanied her for many of the conference evening parties and socials, and took her on various tours of Durban. At a cost of R300 per night, or about $50, McGowan spent about half of the money she would have spent at the conference’s official hotel accommodation and yet had a more personable and varied experience of Durban. McGowan’s Soweto tours, including accommodation, pickup and transportation to the airport, was R500, for two days and one night, or about $83, savings that ultimately gave her more options for her entire travel package. By contrast, on her first night in South Africa, McGowan spent R550 or about $91 on a bed and breakfast in Melville, one of the trendy White neighborhoods in Johannesburg.

It seems that McGowan and other tourists – Black and White – are finding that experiencing Soweto and the real South Africa can be both cost-effective and personally rewarding by tapping into the spirit of “Ubuntu,” or African love and community, through the personal networks of Black South African tour operators. When she left for South Africa, McGowan had only two contacts and some far-sighted ideas about what she wanted to encounter; she returned home a much wiser woman, knowing the depth of the African heart.

To learn more about Johannesburg and Soweto, check out:www.joburg.org.za, www.imbizotours.co.za and www.face2face.co.za.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home