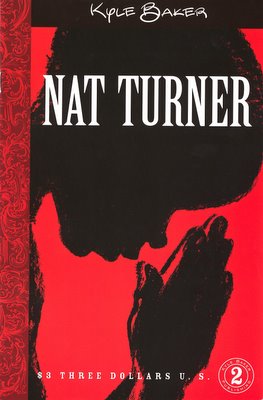

Kyle Baker: A Contemporary Vision of Nat Turner

.

I have't read a comic book in years, but reading this and interviewing Kyle Baker was a fantastic experience...

Kyle Baker’s Contemporary Vision of Nat Turner

Kyle Baker is at it again.

As if his renown as an animator, cartoonist, illustrator and one the comic industries finest artists weren’t enough, the multi-talented writer is turning his prodigious creative energies to writing a graphic novel about the infamous slave rebellion leader Nat Turner.

But perhaps this is expected of someone who helped pioneer the graphic novel art form itself with such treasured gems as the hilarious hip hop critique “Birth of a Nation,” sophisticated social satires like “Why I Hate Saturn” and “The Cowboy Wally Show” and a comic book version of the Bible’s King David. It seems that Baker ‘s consistency lies in his penchant for taking his readers and fans beyond the expected boundaries of his previous works.

For people who haven’t touched a comic book since fourth grade and believe that comics can’t take on serious subjects, think again. Ever since Art Spiegelman broke new literary ground with “Maus”—a graphic novel about his father’s harrowing experience surviving the Nazi Holocaust—graphic novels have set the publishing world on its head. Taking his inspiration from Spiegelman, Baker was one of the first to experiment with the graphic novel format in the mid-80s with “The Cowboy Wally Show,” which one reader called “the single funniest graphic novel ever written.”

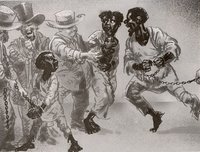

But Baker’s “Nat Turner” series is anything but funny. Nat Turner, of course, has a curious and enigmatic place in our nation’s history. Like John Brown, Denmark Vesey and other slave rebellion leaders, Turner was caught up in the injustices and emotional upheavals that would eventually spark the Civil War. William Styron fired up the American imagination with his Pulitzer Prize winning “The Confessions of Nat Turner,” in which he, a white southerner, took artistic liberties to write from the psyche of a 19th century slave,

Baker’s “Nat Turner” is quite the opposite of Styron’s. Between beautifully vivid, explicit artistic images there is no dialogue, save the actual writings from Nat Turner himself, as told to Thomas R. Gray, the sympathetic attorney who recorded Turner’s last words and confessions in his jail cell as he awaited execution. The result is an extraordinary historical journey that goes back in time to the capture of Nat Turner’s mother in Africa and her horrid slave ship journey through the “Middle Passage,” and on to the story of Nat Turner’s childhood, youth and eventual rebellion.

Baker sought to avoid some of the controversies that followed Styron’s book by adhering to original sources for his story.

“Everything in the stories is actually true—they happened to somebody. A lot of the experiences aren’t particularly well-documented just because they were slaves,” Baker says, with an earnestness that belies his lighthearted sense of humor and irony. “I have a lot of books, and during the Depression there were a bunch interviews done with slaves through the WPA, and they were an excellent source. I’m trying to stick with primary sources because it is such a controversial subject and there’s also been a lot of misinformation written about Nat Turner too, just over the years.

“You can’t argue with actual quotes. You might argue with whether what that guy said was accurate, but you can’t argue that Nat said it, at least.”

“Nat Turner” stirs turbulent emotions as it carries the reader through the trials and tribulations of slavery. The drawings are black and white—revealing Baker’s amazing power of illustration—and vibrantly dramatic, yet starkly visceral and haunting. I found myself returning to the images again and again, reliving events, absorbing the story and developing an unusual affinity for the characters. It’s been many years since I flipped through a comic book, and “Nat Turner” was a pleasurable return to a fascinating—if under appreciated—media.

Baker finds the ambiguity of Nat Turner as a historical figure is perplexing. African Americans and white Americans often have very different views of Turner, and that confuses and fascinates him.

“One thing that I had encountered before I started the book was that every time I told a black person I was writing a book on Nat Turner, they’d get very excited and say, ‘That’s a terrific idea, I can’t wait to see it,’ “ Baker explains. “And whenever I’d tell a white person I was doing a book on Nat Turner they had no idea who Nat Turner was.

“I thought it was very interesting that there’s a guy like that—you ask almost any black person who he is, and he’s a hero. And one of the things that really fascinates me about the guy is that he is controversial and I honestly don’t know why.”

Baker uses his artistry to paint a broader canvass of slavery itself, and while he is known for his deft linguistics and wry sense of humor, “Nat Turner” is more of a sparse, Zen-like journey through historical records and collective images of the “peculiar institution.” He considered including more dialogue, but since he decided to confine his work to historical sources, he felt some of the dialogue could actually diminish the impact of the story.

Baker also pointed out that he had to put more into the art to convey what a character is thinking and saying to compensate for the lack of dialogue.

“If I had added dialogue, it would have had to been in a slave dialect, which is very hard to understand anyway, so I couldn’t see how it would help the story. When I read some of those old things written in dialect, it’s like they almost didn’t speak English,” Baker explains, adding that it’s harder to make the characters sympathetic if the reader can’t understand the narrative. “Slaves were uneducated. They talked like you see in those Mark Twain books. I just felt it real distracting—it’s another problem for the reader to deal with.”

While Baker is held in high esteem in the comics world (he received the Harvey Award and the Eisner Award, considered the two top honors of the industry), he still faces certain editorial battles when he ventures into new experimental territory. He decided to circumvent potential conflicts by self-publishing “Nat Turner” through his own company.

“When you’re signing the contract (with a publisher) you’re taking a guess, because you haven’t written the book. I often get into trouble because as it gets nearer the deadline I realize, “Oh God, this is lot more work than I thought,” Baker pointed out, with his regular chuckle. “In the case of Nat Turner, that’s exactly what happened. The comic books were originally supposed to be 32 pages, but as I was doing them, I felt it really didn’t work at that length, and they needed to be 48 pages. And even that would’ve gotten me fired.

“And then bringing it in late (would be a problem). When I’m working on something like Batman, I can’t get away with that.”

Beyond extending the length of the book and the time he spent working on it, Baker is also choosing to break the format mold with “Nat Turner.” He says an average Superman comic book has six to nine drawings per page, while “Nat Turner” has far more variation, and corporate publishers might have a hard time accepting the project.

“I think if you go into a publisher that traditionally is used to seeing 5 or 6 drawings per page and you bring in one drawing on a page, with no color and no dialogue, it looks you’re trying to pull one over on them,” Baker said, bursting with laughter. “It looks like I’m trying to work less, which isn’t at all the case. The reason I’m doing less drawing per page, is because I want to spend more time per drawing.”

Apparently, the formula is working and the response has been positive. Baker has published the first two comic books in what will eventually be a series of four, and the first one sold out, while the second is also selling out fast. After the final two are printed, the entire series will be published as a graphic novel. Baker will not reprint the comic books, and hence they are becoming collector’s items. He expects to complete “Nat Turner” within two months, although the book is already available in pre-orders on the Barnes & Nobles web site. He started “Nat Turner” around June, 2005, although he conceived the project a couple of years before that.

Baker believes his innovative marketing strategy is helping popularize the graphic novel version, although he feels “Nat Turner” can reach a far wider audience than the young males who typically frequent comic book stores. People who buy and trade comic books aren’t necessarily representative of the kinds of readers who will likely find a Nat Turner graphic novel appealing.

“The thing about the kind of stuff that I tend to do for comics is I’m trying to push the envelope. But the problem is regular readers don’t want the envelope pushed. The people who read Spider Man every week aren’t saying, ‘Boy, I really wish I could have a Nat Turner comic book,’ “ Baker says, with his trademark chuckle. “The reason its being done this way now is because I’ve been in this business for 20 years. I happen to know the distributors and retailers, and now I’m trying to get more into schools and bigger book stores where I think the audience is going to be.”

Depending on the success of Nat Turner, Baker is considering writing other historical graphic novels that might be suitable for teachers and schools. The 40 year-old lifelong resident of New York City has plenty of options in comics, cartoons, film and animation. He recently worked on Shrek II, providing character development for the Eddie Murphey’s donkey. Baker also worked on “Looney Tunes: Back in Action,” with Brendan Fraser, Bugs Bunny and other Warner Brother’s cartoons, where “they spent millions of dollars on it and had tons and tons of meetings and they were wrong.” His experience with the Bugs Bunny movie reinforced his concept of not being afraid to test his own ideas independently in the marketplace.

Baker’s old friend, film director Reginald Hudlin—who worked with Baker and Aaron MacGruder of the Boondocks cartoon series to create “Birth of Nation”—recently became the head of entertainment at BET, and Baker says they are planning a television animation project. But he’s a little concerned about the uncertainty of the budget, which he believes will have a big impact on the quality of the final product.

“I think with TV and video the more you spend, the better it looks. The people he’s hiring are all very good, so it should be okay,” Baker opines, pauses for a moment and laughs. “If the budget’s not that good, I just won’t be that excited about it, but I’ll still do it.”

“The Bakers,” a comic book and graphic novel series about his wife and three children is another one of his self-published projects that is close to his heart. His wife Liz says, with a slightly strained ambivalence, “He gets paid to make fun of me. Very few people can get away with that.”

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home