Es'kia Mphahlele's African Literary Journey

...

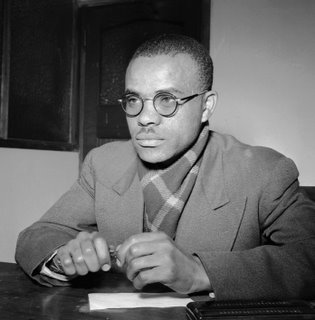

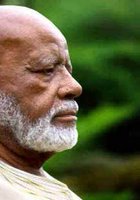

Es'kia Mphahlele in 2005 (left) as a dapper journalist in the 1950s. This photo is courtesy of Jurgen Schadeburg, who captured Black South Africa during the Drum era. Check out his web site--it's an amazing visual journey.

Once again, this article is part of my Eye on Africa series. I feel honored that I had the opportunity to meet and interview Ezekiel Mphahlele. He is truly one of the giants of our African cultural leaders, and given his age, this recent visit to the States may be his last--he doesn't travel here very much. Meeting Es'kia reminded me somewhat of a chance encounter I once had with James Baldwin 22 years ago; they both had a powerful presence, a profound wisdom and soft-spoken intellect that is subtle yet overwhelming. I would have loved to have spent more time with Es'kia (or for that matter, James Baldwin), but alas, there never seems to be enough time to spend with these great "fundis." Their writings live on for future generations, but sadly, their time is limited in this world. In this article I wanted to present Es'kia in the broadest context of his life, and to hint at his ideas of "African humanism" which I believe can form the basis of a viable and creative African educational system.

Es'kia Mphahlele's African Literary Journey

“The minds I would be dealing with were already unchained by their own effort. Give people a poor education and the mind will soon find a way out. Revolt is then inevitable. No, the mind cannot be chained forever.” - Es'kia Mphahlele

Throughout my experiences and travels in Africa, I have followed the shadow of Es’kia Mphahlele--his reflection, traces of his footprints—until one fine, late August day, I met face to face with the world-acclaimed novelist, educator and African philosopher. The 85 year-old former University of Denver professor lives in Johannesburg, South Africa, and was in Denver on a rare trip (and perhaps his last) to the United States. I had the good fortune of being introduced through a mutual friend and spending an afternoon of evocative conversation in the backyard shade of a quiet Park Hill home. It was an extraordinary encounter.

Ezekiel “Es’kia” Mphahlele is one of Africa’s most revered writers and scholars, known both for his literary works as well as for his activism in arts, cultural and educational matters. He was initially trained as a teacher, but after he spoke out against the inferior standards of “Bantu” education the apartheid government banned him from teaching anywhere in South Africa. Subsequently Mphahlele became a political reporter and fiction editor for Drum, a continent-wide African magazine that printed daring political exposes by brilliant investigative journalists, peppered with colorful features and creative writing styles blending English with African idioms and narratives. Drum mirrored a literary renaissance in the 1950s, an era when South Africa was burgeoning with creative energy in the music and the arts. (Interestingly enough, a recent South African film, Drum, by director Zola Maseko and starring Taye Diggs, tells the story of Henry Nxumalo, one of the most popular Drum journalists who was found murdered in Johannesburg.) Notwithstanding the attention he and others received through Drum, Mphahlele aspired to be a writer, and after he finished his Masters degree at the University of South Africa in 1956 he went into exile with his wife Rebecca and their three children.

Mphahlele began teaching in Nigeria, later saying that “West Africa gave Africa back to me,” awakening him from the alienation and deep-rooted traumas of apartheid. The 1959 publication of his autobiographical novel, Down Second Avenue, drew worldwide interest in Mphahlele as a writer, and focused a powerful spotlight on the internal dynamics of South Africa as it steadily drifted toward greater racial oppression and greater world isolation. Now a classic of African literature, Down Second Avenue had successful printings in English, French, German, Russian, Dutch and Japanese, which reflected the impact and international popularity of the book. Mphahlele’s second novel, The Wanderers, a story chronicling the experience of exiles in Africa, earned him a nomination for the Nobel Prize in literature in 1969.

Mphahlele thrived on his teaching activities in Nigeria, but he also found himself drawn into a whirlwind of creativity activity among West African writers and artists such as novelists Wole Soyinka, Chinua Achebe, Ngugi Wa Thiongo and Amos Tutuola, sculptor Ben Ewanwu and painters Demas Nwoko and Uche Okeke. Mphahlele felt he had been plucked from a South African literary renaissance only to be dropped into the heart of a West African cultural renaissance. He was appointed director of the Congress for Cultural Freedom in Paris, for which he traveled and worked extensively in Kenya, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Ghana, Nigeria, Cameroon and Uganda, in addition to lecturing throughout Europe. At the end of his term with the Congress, while teaching at the University of Nairobi in 1965, Mphahlele was offered a teaching fellowship at the University of Denver and an opportunity to earn his PhD, an offer that he gladly accepted.

By the mid-1970s Mphahlele had built a thriving career in academia and a comfortable life in American suburbia, but the “tyranny of place” dominated his heart and mind. He could feel the land of his forefathers calling him, and he yearned to make his teaching and writing relevant to the actual conditions of life in South Africa. In August, 1977, barely a year after the Soweto riots, and less than a month before the death in detention of Steve Biko, the Mphahleles returned permanently to South Africa, exchanging their British passports for the infamous South African passbook ID, the “badge of oppression.” And this very fact makes Es’kia Mphahlele’s life distinctly different from most South African exiles, who generally left the country in the 50s, 60s and 70s and returned in the early 90s, after Nelson Mandela was released from prison and Black political parties were unbanned.

The return to South Africa was not without its controversies. Many of Mphahlele’s fellow exiles—prominent political activists, writers, musicians and poets—told him that going back was a mistake. Not only was he possibly endangering himself and his family but, they also argued, that returning at that time would be a propaganda coup for the South African government, which would then appear to be more liberal and open in its policies. Mphahlele dismissed these arguments, but he also paid heavy prices for his return. Within a few months of being back in South Africa, his son Puso began to get his first ugly, bitter tastes of racism apartheid style. He was not conditioned to the survival instincts of living under apartheid, and they feared for his safety. The older Mphahlele children had already become accustomed to individualistic, independent American lifestyles, and so Es’kia and Rebecca sadly gave their son “back to America.” After some discussion, they all agreed that it was best for Puso to live with his sister in Washington, D.C. and finish his high school education in the United States.

Mphahlele had returned ostensibly to assume the chairmanship of the English Department at the historically Black University of the North, and the teaching staff voted unanimously for his appointment. But once again Mphahlele was destined to confront the face of government repression, as the Minister of the Department of Education vetoed his appointment, leaving him jobless. White supremacist politicians could not tolerate the idea of an African being the head of a Department of “English,” leading a White staff that was actually much less qualified. Despite the rebuke (and thinly-veiled retribution) of apartheid officialdom, Mphahlele had the last laugh. He was eventually asked by the vice chancellor of the private University of Witswatersrand—South Africa’s most distinguished university—to become the chairman of their new Department of African Literature.

In the South Africa of 1977—as compared to 1956, the year of his exile—Mphahlele found worsened conditions in the urban townships (Soweto was “monstrously slummier”) and an educational system ravaged by the sub-standard “Bantu” apartheid program. He traveled around the country in various capacities lecturing and teaching new ideas for transforming African education based on “African humanism,” an overarching concept that he felt was valid for the continent as a whole. He often drew large, overflowing crowds of people, young and old, students and non-students, eager to hear from the worldly scholar and Nobel prize nominee who had returned to be with his people and fight the system from within. He was held in high esteem and was a contemporary African prophet and hero to many.

Mphahlele’s African humanism embodied the ideal that Africans should express their own unique approach to education, getting to know themselves and their continent through a study of African history, religion, cosmology, literature and the arts, before moving on to other areas of world knowledge. Although he never drew the apparent parallel, Mphahlele’s African humanism pedagogy presages a comprehensive introspection of African traditional culture, not unlike the Edo period in Japan, where the Japanese barred Europeans from their society and experienced a flowering of their classical culture while simultaneously learning Western technology and economics.

Over many years, I slowly discovered why Es’kia Mphahlele is so revered by South Africans, the world academic community and Africa’s intelligentsia. Sitting in the shade of a friend’s plum tree, I had come full circle, and I could not help but love the small, soft-spoken literary giant. We talked for quite some time about his days with Drum magazine, his years in exile, trends in African art and literature and the future of South Africa and the African continent as a whole. His aged, graying eyes belied the intensity of his intellect moral courage and fierce honesty; his words conveyed the hard-won wisdom of years of travel, copious study and astute human observation.

Over many years, I slowly discovered why Es’kia Mphahlele is so revered by South Africans, the world academic community and Africa’s intelligentsia. Sitting in the shade of a friend’s plum tree, I had come full circle, and I could not help but love the small, soft-spoken literary giant. We talked for quite some time about his days with Drum magazine, his years in exile, trends in African art and literature and the future of South Africa and the African continent as a whole. His aged, graying eyes belied the intensity of his intellect moral courage and fierce honesty; his words conveyed the hard-won wisdom of years of travel, copious study and astute human observation. I asked Es’kia if he felt Africa had a living spirit, and if that spirit touched him or spoke to him in some way. His poignant answer was timeless and inspiring, in light of the overwhelming darkness and strife South Africans, African Americans, and many African people have faced in recent history.

“Yes, Africa speaks to me, because I listen too much to the wild voices of now, of present day politics and ethnic problems and conflicts. (But) I (also) listen to the subterranean voices, the voices coming from the past, from my forefathers and our ancestors. That’s how Africa speaks to me. Never mind the political noises that one hears, this way or that way. I’m talking about something much more solid, as well as spiritual. And there are ugly things happening in African countries. The poverty of Africa touches me deeply, especially because our leaders seem to be so impotent in dealing with it. There’s a good deal of corruption among some African leaders who simply want to have power and wealth. They don’t care two hoots about what happens to the people, and that is the sad part of it. But if you stop and listen to the voices of ancient wisdom—and you hear the voice in the metaphors of our languages and in the mannerisms in which we as Africans approach each other... If we listen to the voices of those forces, you get somewhere. You realize that you have some protection from other kinds of foes and forces that work on you.”

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home