At the Edge of Time in Zimbabwe

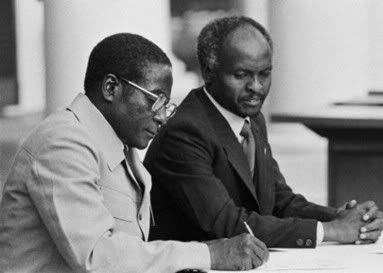

Robert Mugabe and Canaan Banana, Prime Minister and President respectively, at a signing ceremony on Zimbabwe's independence, April 18, 1980.

At the Edge of Time in Zimbabwe

I first met Sulieman Dauda in Yeoville, a hip Johannesburg neighborhood that was a favorite hangout for journalists, actors, musicians, activists, travelers and just about anyone who was looking for a good time. My good friend Jim Harris, a jazz musician, labor organizer and a respected elder of the African American expatriate community surprised me when he said he had an old friend from Denver who was coming into town for the April 1994 elections. African Americans were a novelty in South Africa back then, few and far between, and I could hardly expect to find someone from my home town.

Jim’s friendship with Sulieman went way back to 1981 and the early years of Zimbabwe’s independence. They both owned beautiful homes in Zimbabwe, and they both seemed intimately caught up in the vortex of energy that birthed the new nation. In Jim’s modest flat, just one block beyond the raucous vibe of Yeoville’s infamous Rocky Street, I was captivated by Sulieman’s easy going manner and his wealth of knowledge and experience in Africa. Often into the wee hours of the night, Sulieman, Jim and I would ramble on about African culture, race, politics and spirituality as we watched news of the national elections and waited for Nelson Mandela’s inauguration ceremony. Jim and Sulieman especially savored the moment; just like years before in Zimbabwe, they once again had their front row seats to witness African history in the making.

Tall and lanky, with a graying beard, wearing a simple T-shirt and jeans, Sulieman Dauda was humble, non-assuming brother, not someone you would expect to be a property owner in the lush and stately suburbs of Harare. His ear-to-ear grin and bright smile seemed to reflect the unbounded joy of the Motherland itself. On the street, Dauda blended in with ordinary South Africans, and you could tell that he could party with the best of them. Somehow I wasn’t too surprised when Jim and Sulieman told me how they befriended Richard Pryor in Zimbabwe and how their hilarious adventures became part of the material for Pryor’s legendary “Live on Sunset Strip” performance. (Jim Harris even went so far as to suggest that Pryor unabashedly stole a few of his choice lines, but I digress…)

Sulieman Dauda had many friends throughout Johannesburg and Soweto, and the three of us all ended up “jowlin” – as they say in Joburg – partying heartily throughout the massive celebrations and elation that permeated the weeks leading up to Mandela’s inauguration. Sulieman went back to Denver after a few weeks, and not long after that Jim and I ended driving across the Limpopo Province and over the border, through to Bulawayo and Harare. Crossing into Zimbabwe at that time one felt a sense of peace that was not present in South Africa, a feeling of calm, patience and ease. In June, 1994 exchange rate of the Zim dollar to the US dollar was 7 to 1; now the exchange rate has exploded beyond the realm of hyperinflation and speculative fiction to an incredible 30,723 to 1.

Times have obviously changed in Zimbabwe. A litany of human rights abuses, a crackdown on freedom of the press, a failing economy, new refugees and displaced communities have marred the reputation of president Robert Mugabe as a hero of the liberation struggle. After reading news reports from Southern Africa, I have often thought about Sulieman Dauda and his extraordinary bond to that beautiful and struggling nation, which not long ago seemed to have all the promise in the world. As a busy landlord, Dauda spends most his time – usually from early mornings until evenings – tending to the duties of his many properties in Denver and his hometown of Gary, Indiana. Recently, in between his demanding schedule, I finally caught up with him to have in depth, detailed conversations about his adventures and exploits in the Motherland. I found his stories compelling, and his experiences and perspectives were refreshing and insightful.

"I knew at the age 16 that I was going to travel to Africa, and I knew I was going to live there,” Dauda said, as we strolled through City Park, taking in the sights and sounds of the Denver Black Arts Festival this past summer. “I had to go and see the truth for myself, and I could see from the books that were available in the late 60s, that they weren’t telling the truth – everything that should have come out wasn’t coming out.”

After a period of radicalization with the Black Panther Party at Wilbur Force College in Yellow Springs, Ohio, Dauda left college and joined the Navy in order to get GI Bill education benefits. Through a long series of events, Dauda ended up at Metropolitan State College in Denver, where he chose to major in marketing and minor in Black Studies. In 1978 Metro offered its first ever educational travel program to Africa, and Dauda was the first student to sign up. While the trip was cancelled for lack of student participation, his teacher and mentor, Dr. Akbarali Thobani, arranged for Dauda to continue his trip with another tour group. Once he was in Africa Dauda could barely contain himself and decided he had to extend his travels beyond the limits of the tour.

“I said to myself I would get off at the furthest point (of the tour), and find my way back to the first point,” Dauda said with a smile and a soft laugh. “That’s what I did for three months. I went from Lagos, all the back up to Senegal.”

Perhaps his most important and telling experience in West Africa happened in Jos, Nigeria, where he met a blind spirit medium who told him, “Go to Zimbabwe, and all your dreams will come true…” The message was confusing, because at the time the name “Zimbabwe” was relatively unknown, as the country was still in the midst of its brutal independence war, and was then known as Rhodesia. But in late 1979 Zimbabwe grabbed more international headlines as the United Nations and the British government brokered an uneasy coalition government agreement that paved the way for free elections. Suddenly Dauda had a sense that destiny was calling him to a mysterious new country with a fascinating name.

At an African Liberation Day rally in New York City in 1980, Dauda listened to Robert Mugabe give a speech about his new country and its new government. Mugabe wanted African Americans to help in building the fledging society, and he told the crowd, “Be ye Africans, come home! Bring your skills to Zimbabwe!” The speech and the event so impressed Dauda that nearly 30 years later he still has the original brochure. Mugabe’s idealism and charisma sealed Dauda ‘s conviction that his future lay in Zimbabwe.

By the time Dauda embarked on his Zimbabwe sojourn a year later, he had taken two more trips to West Africa, and as a veteran traveler had learned how to make friends and barter, sell and trade his way through the region. Not long after arriving in Zimbabwe, he became friends Sam Mashata Paweni, a businessman that needed his marketing and management skills, and Dauda found himself writing proposals and tenders for to provide supplies and requisitions for various businesses, government agencies and the military. Their partnership was so successful that Dauda describes their business alliance as a “Halliburton” of Zimbabwe.

Paweni became one of Zimbabwe’s wealthiest men, and Dauda was responsible for 350 employees and an array of companies, departments and divisions. While Africans were sometimes a little suspicious or wary of African Americans, Dauda was able to turn his unusual circumstances to his advantage in affecting the way he was perceived by Africans.

“A lot of times they are just as ignorant about us as we are about them. It’s kind of difficult to overcome that, knowing that ‘here I am in Africa, and I’m completely at their mercy,’ ” Dauda said, adding that his personality and his accent helped him transcend awkward situations. “The street part of me came out over there. Without that, no telling what would have happened. I know that a lot of times you just gotta talk until they tell you to shut up. They just want to hear you talk.”

Dauda took a few cues from Jim Harris, and parlayed his job and earnings (and fall in property values due to white flight) into purchasing the home of his dreams, a lovely 3 bedroom dwelling with a cozy fireplace, perched on the edge of hill in cove, with a panoramic view and a river running through it.

“It looked like a golf course when I first saw it. It was beautiful,” Dauda says, and then suddenly his tone of voice changes, as he pauses after his long “stream of consciousness” descriptions of the path leading to his early years in Zimbabwe. A brief silence overcomes him, as we watch people moving to and fro through the various Black Arts Festival booths and stalls, eating, laughing and meeting old friends.

“Man, now you’re gonna sit up here and make me cry,” he says, smiling, with a touch of laughter and sadness. “You know why? I’m remembering all these good times about Zimbabwe and how much fun we had. I never laughed so hard in my life at all the funny stuff that went on.

“Meeting new people was my favorite thing. Every time you meet somebody new they invite you over to their house, and then you’ve made a friend for life. You sit down at their house, eat their cooking, and spend the day with their family…”

But the good times and the good feelings had their limits. The goodwill and lack of recrimination that had manifest during Zimbabwe’s early years was doomed to evaporate in the face of South Africa’s hostility and repeated attempts to destabilize its democratic neighbor. Towards the end of the “independence hangover,” racism from South Africa seemed to spill over into Zimbabwe, poisoning the atmosphere and creating a sense of fear and distrust.

“(In the early days) everybody had money, and gasoline was plentiful, and food was plentiful. You could take a dollar and buy a steak as big as this plate, and that would be enough to feed 5 or 6 people,” Dauda said, adding that in 1980, the Rhodesian dollar was stronger than the US dollar, and the two currencies traded almost one to one for about four or five years. “Then everything started going backwards. The first time I ever experienced a petrol shortage in life was in Zimbabwe. But it wasn’t because of Mugabe – it was because of the white South African blowing up the oil pipeline.”

The South African apartheid government organized a number of bombings, including the Zimbabwe African National Union – Patriotic Front (Zanu-PF) party headquarters in Harare. The failed assassination attempt on Mugabe killed mostly innocent civilians. Yet the most notorious event was the covert operation that resulted in a plane crash and the death of the popular Mozambican president and revolutionary leader Samora Machel. Dauda said the insidious South African attacks resulted in open clashes between Blacks and Whites on the streets in Zimbabwe.

“With the people in Zimbabwe, oh man, there were riots! They burned down the South African embassy, they burned the South African Airways building,” Dauda explained. “They were running up and down the streets slapping White people. Man, they knocked the sh-t out of them. White people were scared at that time, and that’s when things started to change. White people started leaving, after the death of Samora Machel.”

In his personal experience of Zimbabwean history, Dauda has as very different perception and understanding of President Robert Mugabe than the current media stereotype. Dauda speaks of Mugabe with reverence and respect for leader who faced a daunting task of building a new nation in extremely hostile and antagonistic conditions. He describes Mugabe as a man who had a lot of enemies and had to worry about his safety. Dauda is keen to point out that the vast majority of the Rhodesian forces were Africans, and thus the nature of the Black-on-Black conflict in the heart of the independence war was more complex than surface appearances.

“You see, it was actually a civil war, Africans fighting Africans. So Mugabe didn’t know who was who or what was what. The only thing he knew about Rhodesian forces was the soldiers had uniforms,” Dauda says, emphatically, his voice rising in emotion. “So his safety was paramount. That’s why he moved around in a large entourage. He had cars in front of him, cars in back of him, soldiers in back of him, driving around in 5 series Mercedes. They called him “Bob Marley and the Wailers” because everywhere they went they had these loud sirens.”

Dauda says his view of Mugabe has not changed, although he believes at times Mugabe has been ill-advised, and some of his cabinet ministers received jobs and appointments they didn’t earn or deserve. He also saw some people’s lives and careers ruined by misinformation given to Mugabe. Nonetheless, he remains a staunch defender of the controversial leader, and sees him “as a true comrade and a revolutionary.”

Dauda concedes that Zimbabwe has changed, and has become less secure and more crime ridden. On a recent trip he was mugged for the first time in Harare, which was a far cry from the time when Dauda walked down all the back streets of the capitol city without incident. He also feels that South Africa, like Zimbabwe, is not as safe as it used to be. Ironically, Dauda claims that he had the best time of his life in apartheid South Africa in 1987. He remembers a White South African border guard saying, “You’re going to have so much fun you’re going to want to move here.” He didn’t believe the guard, but the guard invited Dauda to come back and speak to him after his trip.

Hanging out with Black journalists, Dauda moved through Johannesburg’s racially-mixed neighborhoods like Yeoville and Hillbrow, and through Soweto’s neighborhoods like Dube and Pimville, and the vibrant but deeply impoverished township of Alexandra. A one month trip turned into three, and when he returned he told the border guard that South Africa was everything he said it would be, only “ten times more.”

“I still lay in the bed and think about that. What’s the difference between then and now? It’s nothing like it used to be. I don’t know what to say – I still had the time of my life,” Dauda says, as he reflects on his adventure under apartheid. “I can’t go there now and have the time of my life. I can’t go there now and have the time of my life – it’s not safe. I couldn’t go to the same border crossing and see that same border guard, because the whole border crossing has changed. It went from being all White to all Black. The people are very ornery…”

Such ironies have not escaped my remarkable friend.