"Lost Boys" of Sudan: Searching for Peace

...

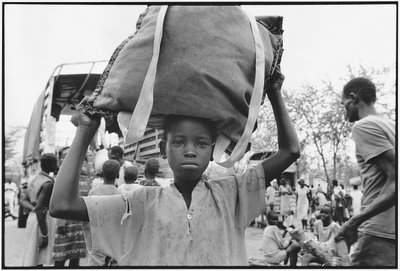

One of the "Lost Boys" of Sudan carrying food at the Kakuma Refugee camp in Kenya.

One of the "Lost Boys" of Sudan carrying food at the Kakuma Refugee camp in Kenya.The “Lost Boys of Sudan” is truly an incredible story. It’s a story about war, cruelty, suffering, endurance, faith and deliverance… In our global village, somehow, the things that happen to James Manyror and Michael Deng are more and more everyone’s responsibility. Meeting and James and Michael was an inspiration---the distance they’ve traveled, physically, mentally, emotionally and spiritually is unbelievable. The world is changing and evolving at a breakneck pace, and some people are caught up in the vortex. James and Michael should be a reminder to us that while mass events are often beyond of our control, individual lives do matter, and we should do what we can to make a difference.

"Lost Boys" of Sudan: Searching for Peace

How does a place of such beauty and history become rife with conflict and suffering? Over the last 20 years Africa’s largest geographical nation has also become home to its most protracted and brutal war. More than 2 million people have been killed and another 4 million displaced in a civil war where accusations of genocide, ethnic cleansing, slavery and crude horrors abound--horrors that are nearly impossible to conceive behind Western TVs, computer screens and the conveniences of modern living.

Most recently, Darfur has commanded world attention, as the combined attacks of the Sudanese military and the Janjaweed militia have bombed, killed, raped and pillaged, carrying out a scorched earth policy that has decimated the livelihood of peaceful, agrarian people. As hundreds of thousands have been driven to destitution and starvation, many world leaders, aid organizations and human rights groups have called for international intervention.

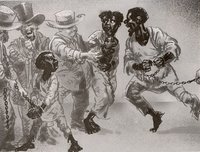

It seems that these massive conflicts, tragedies and displacements have their own special names and places in the history of the African continent. There is the Maaf or the great crisis of slavery; the Mfecane or Defacane, the vast destruction and migrations of tribal groups in the wake of Shaka Zulu’s ruthless expansion; and now a new Diaspora of African Sudanese seeking refuge from continent’s latest conquerors.

But even before we began to hear about the problems of Darfur, another extraordinary saga of suffering was emerging from the Sudanese north-south conflict. The desert of Sudan and Egypt has been a land of epic migrations and the scene of biblical exile and deliverance—and it seems that in our modern times we have witnessed a new mythical tale in the sad story of the “Lost Boys of Sudan.”

In 1987, the Sudanese government—in coordination with loosely organized militias—intensified its bombing raids and attack on towns and villages the southern region, killing adults and raping and enslaving women and young girls. Thousands of the male children from these pastoral regions were typically herd boys who tended goats and cattle on the outskirts of their villages and by chance survived the devastation. Suddenly homeless orphans, these boys gradually coalesced into larger and larger groups seeking to escape the violence and possible enslavement or conscription. Ranging from about 5 years old to 13 or 14, the wandering bands of “lost boys” had no idea of the terrifying ordeal that lay ahead of them. Originally some 26,000 (according to UN estimates), less than half would survive the agonizing journey on foot that would eventually cover nearly 1,000 miles of desert and months and years of wandering from one village or temporary refugee camp to another.

Dogged by hunger and thirst, the Lost Boys ate leaves and wild berries and sucked water from mud and desert plants to stay alive. Sometimes the pain was overwhelming and some of the boys just collapsed to the ground from exhaustion, or slowly lagged behind, becoming easy prey for lions. When the smallest boys were in too much pain to walk, some of the older boys would pick them up and carry them on their shoulders. Sometimes the Red Cross helicopters dropped food and supplies to them, but aid organizations were unable to land because of the fierce fighting in the region. For the most part, the Lost Boys were on their own.

The boys walked for several months across southern Sudan and into Ethiopia, where they lived for three years in various refugee camps. But fate was not on their side, as Ethiopian insurgents staged a coup d’etat in 1991 and the rebel military forces chased the boys out. In their desperate attempt to escape Ethiopia, many of the Lost Boys drown in the River Gilo, or were eaten by crocodiles or shot.

For more than a year the boys walked back into Sudan, and then south to Kenya, where they finally found relative stability at Kakuma Refugee camp in 1992. Over the past 10 years Kakuma has grown into one of the world’s largest refugee camps and is now home to more than 80,000 dispossessed people from Somalia, Ethiopia, Rwanda, Burundi, Uganda and Congo, in addition to the Lost Boys and other Sudanese. While Kakuma provides some security and basic health and educational services for the boys, it is a desolate environment of sweltering 100-degree desert heat, tin-roof mud slab homes and pit toilets. The refugees are unable to cultivate their own crops, and must rely on a low-calorie one meal per day food ration. But the Lost Boys at Kakuma were grateful for their survival, and are eager to take advantage of primary education classes and English lessons in hopes of a better life.

James Manyror knows firsthand about the terrifying experience of the Lost Boys. But sitting in his comfortable Aurora apartment, with his 49ers jersey, baggy jeans and basketball sneakers and the TV blaring ESPN NBA highlights, you would never guess that he was among the thousands who made that harrowing journey through the desert. Manyror looks like an ordinary African American teenager or hip-hop kid. His dimpled smile and easy going laugh show no signs of someone who lost his innocence and childhood in the Lost Boys’ ordeal. If you ask him about the past, he’s eager to tell his story and share his amazement where life has taken him.

“Life was really a struggle. When I think back then, it looks like a nightmare—you can’t figure out where you are. You can’t imagine that year,” Manyror said, as his voice suddenly becomes animated. “I never thought that I could sit here. on a couch like this, in a place like this and go to school. We really struggled and we didn’t know where we would end up.

“Sometimes trying to explain it is really difficult. There was no food some days; there was no water some days; sometimes you are sick and you don’t know if you’re going to stay alive.”

Manyror’s roommate Michael Deng is also a Lost Boy from Paireng, the same village that Manyror was also born in. They come from an isolated rural area with no electricity, no TV or radio, no running water. The two boys made the long journey together in allied groups, and have a very deep bond and friendship; they came to Denver together from Kakuma in 2001. In four years they've gone from learning how to use can openers and telephones to attending college and mastering the look and feel of American youth. Deng is more introspective and reserved, but with his fly shirt, crisp pants, handsome boots and smooth haircut, he looks ready to hit Pierre’s Supper Club or the Casbah on the prowl. But when he speaks, Deng appears serious and thoughtful, carefully considering his words.

“You can’t imagine it,” Deng answers ponderously, replying to my question about his experience during the war years. He speaks slowly and shakes his head in disbelief. “I can’t explain it. It would take an entire year or two years. It was such a large history that you cannot cover it in one day.”

Manyror then proceeds to describe the general events of their great trek. The government attacks in 1987, their escape to Ethiopia, being chased out of Ethiopia back into Sudan, and finally walking all the way across the Kenyan border to Kakuma. He said they had nothing when they left Paireng, but sometimes people would give them supplies along the way. Language was often a barrier and at times they could only communicate with hand gestures; sometimes villagers were openly hostile. One of his worst experiences happened when they were leaving Ethiopia and a local gang opened fire on them.

“After we left Pinchalla, when we were in Kopita, we were attacked by local villagers—it was a very tragic attack. One of my friends was killed that night—oh man, I was so scared,” Manyror said with a tremble in his voice, adding that he had many nightmares long after the event. “They started shooting at night. Nobody saw them come up to us.”

Deng seemed calmer and less traumatized by the attack, and explained that the villagers were “shooting randomly” and those who happened to remain prone, close to the ground, survived; the unfortunate boys who stood up and ran were killed. Manyror was terribly shaken by the loss of his close friend, who they buried later that day.

“I think it was his day to go,” Manyror shrugged.

When I asked both young men about the roots of the conflict and the perceived racial differences between the Sudanese Arabs and Africans, Deng let go a bitter, sarcastic laugh, again shaking his head in disbelief. Manyror however, was more inclined to discuss the political context.

“When you say you don’t see a (racial) difference between (the Sudanese) Arabs and Africans, you are right. But political differences play a role. It comes to religion—the Arabs think that they are Moslem, and the others are infidels,” Manyror pointed out, explaining that the Arab government has imposed Islamic fundamentalist Sharia law and controls job opportunities and economic development. “Some who are a little lighter think they are separate from the south, but it is heritage that is the biggest difference.”

Deng and Manyror are from the Dinka tribe, the largest ethnic group in Sudan, and they both hail from the Ruweng clan of the Dinka. Like many of the Lost Boys, both young men are not quite sure of their ages or birthdays. Manyror says he was born in 1979, and was 12 or 13 by the time they made it to Kakuma in 1992. Deng says he was born in 1980.

True to his solemnity and contemplative character, Deng speaks of becoming a priest or pastor. He works during the day at Safeway and takes theology courses from the Catholic Church at night. Manyror works as a Certified Nursing Assistant—he studied nursing at Aurora Community College—and intends to transfer to a university to earn his Bachelor degree. Both young men say they are so busy with school and work that they have very little time for TV, movies web surfing or other kinds of youth entertainment.

Manyror returned to Kakuma for two months in April and May of 2005, and he has now become consumed with a vision of starting an organization to help other Lost Boys at Kakuma. There is a continuing influx of refugees from Sudan, and after talking with Kakuma officials and local church groups, Manyror would like to assist in a project to construct 10 dormitory buildings and 10 classrooms for some 200 young orphans who are now semi-permanent residents at the camp. Like Manyror and Deng, the orphans will receive some education, and many of them may be resettled in the United States, Great Britain, Australia and other countries. Manyror calls his organizations the Sudanese American Orphaned Rehabilitation Organization (SAORO) and has applied for tax-exempt status as a non-profit. The organization plans to launch its web site—www.saoro.org—in March.

Manyror is very excited about the prospects for SAORO and he believes he is in a position to make a difference for Kakuma, which he describes as a “horrible”—if relatively safe and secure—place. He hopes more Americans will learn about the crisis in Sudan and will help the plight of Sudanese refugees.

“People in the United States hear all kinds of stories in the news—good stories and bad stories. If they don’t hear these stories, they won’t know what is happening.” Manyror explained, saying he believes people of “goodwill” can help the Lost Boys. “I think for me, not to get this story out, is not an option.”