Motherland of the Mind, Body & Spirit

Africa, of course, is a continent, a location on our planet; but there are many dimensions and many ways of accessing Africa. While people jam to the latest pop dances and grooves, it sometimes escapes us that the common practices of African American popular culture or African traditional culture can be the gateway to a profound inner wisdom and intuitive knowledge. Teachers like Maurice Haltom – or “fundis” as they say in South Africa – remind us that we can find an infinite world of truth and beauty through the Motherland within ourselves.

Motherland of the Mind, Body and Spirit

Jamming to the latest R&B or hip-hop joints, or marveling at the grace and beauty of dancers in an Usher, Ciara or Aaliyah music video, we are captivated by a certain style and grace that is Africa. But it sometimes escapes us that the inherent sense of movement that created an endless variety of fascinating dances can also be the gateway to a deep intuitive wisdom, in much the same way that yoga in India - and Kung Fu, Tai Chi and Qigong in China - are profound spiritual mind-body disciplines.

Indeed, just as African American pop dances are varied expressions of a certain inner theme or quality, and jazz music can yield many different renditions of a “standard” piece, Africa itself has the endless ability to adapt, absorb and morph its great identity into a multiplicity of manifestations. Sometimes certain teachers are able to illuminate these associations, to remind us that Africa has a richness of knowledge, congruities and connections that extend far beyond surface appearances.

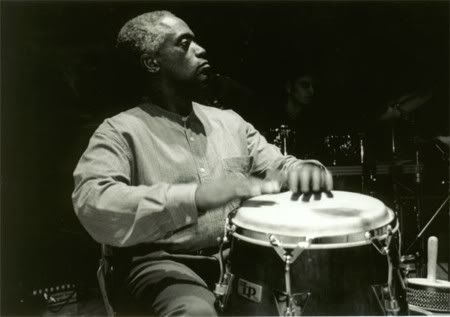

As one such teacher, Maurice Haltom has never set foot in Africa, yet he carries the Motherland in his heart and mind, and throughout his whole being. In fact, it seems that virtually all of his aspirations and life’s work have been dedicated to exploring the profound wisdom and cultural connections underlying African music, movement and dance.

As a musician, Kung Fu and Tai Chi master, yoga instructor, psychotherapist and healer, Haltom has mastered an extraordinarily wide range of disciplines related to fitness and mind-body awareness. At Cornell University, the Omega Institute and in countless seminars and workshops from New York to California and the Caribbean, Haltom has taught students from all racial backgrounds and walks of life about health, healing and spiritual consciousness through African-based traditions.

After more than 30 years of teaching, Haltom – who currently lives in Ithaca, New York and runs the Cayuga Center for Wellness and Healing Arts – has developed distinctive innovations synthesizing spiritual practices from India and China with fundamental aspects of African culture. His unique perspective has evolved from amazing life experiences spanning decades of encounters with remarkable teachers and mentors.

Perhaps his journey was sparked in the late 50s, when Haltom was high school student in Berkeley, California and his family lived a few blocks from the coffeehouses of beatnik poets, who at the time were sowing the seeds of the radical social movements of the 60s. Unbeknownst to his parents, young Haltom’s talent for African drumming was drawing him into startling new relationships and outlooks.

“The beatniks were vital and interesting to me because they appreciated the bongo drum. They would have the bongo drum playing behind their poetry and that’s where I got my first stage appearances – behind the beat poets,” Haltom explained, adding that his parents thought he was out running his newspaper routes. “In the meantime I’d be at the coffeehouses really getting my mind opened up. I could pop in there and find a whole different reference point. My own peers were no longer my reference point.”

The beatniks had an “artistic, European and French non-materialistic orientation” that Haltom says encouraged him to look for novel philosophies and alternative perspectives to mainstream ways of thinking.

After graduating high school, Haltom enlisted in the Air Force and was stationed in England when he met Aubrey, an African-American drummer and flutist who also practiced Karate. Haltom was intrigued by Aubrey’s ability to bridge the avant-garde world of jazz and martial arts; his new mentor introduced him to salsa music and Latin and Caribbean drumming styles, as well as the discipline of Oriental fighting techniques. But as Haltom delved further into Karate, he felt there was a natural connection between African dance movements and the martial arts, and he kept trying to create a more fluid fighting style, which ran against the grain of Aubrey and his other Karate teachers.

“There was a certain grace and a certain rhythm I wasn’t trying to get to and they couldn’t stand it,” Haltom says.

During the height of the radical changes of the 60s – from 1964 to 1969 – Haltom played music while immersing himself in the exciting social scenes that were developing in London, New York City and San Francisco. Haltom played for a variety of bands in California – including The Loading Zone, Kwandidos and Tower of Power – that at times opened for rock music icons Jimi Hendrix and Jefferson Airplane at the Fillmore in San Francisco. During one of his rehearsals, an Afro-Latin percussionist who learned that Haltom was interested in martial arts challenged him to spar. Haltom later found out that this non-assuming, talented musician had acquired the nickname “Sal the Assassin.”

“He took me outside and we spread out to spar and he just took me back to school in a way that I just could not ignore,” Haltom says, unable to suppress his own hard, hearty laughter. “And he did it in a way that like dancing. He was into music and dance, and he was an alcoholic at the time, but he had a mind that was really open. He was trained by a Kung Fu master and I asked him to take me to his teacher.”

As a result of his “schooling” by “Sal the Assassin,” Haltom then began studying with Kung Fu master Steven Hou. Kung Fu, with its continuous, circular movements, seemed to have the fluidity that Haltom had been yearning for. Not long after beginning his tutelage with Hou, Haltom also witnessed the Chinese Dragon Dance, and he saw a cultural connection between China and Africa that he had intuitively sensed. While unmistakably Chinese, the Dragon Dance – with its colorful tassels and loud firecrackers symbolizing the thunder of springtime – also has an essentially African drumbeat and rhythm. Haltom noticed that even the movements of the Dragon dancers themselves resemble African dance styles.

With time, Haltom became more and more aware of fundamental, archetypal expressions of African movement and dance, seeking to integrate these movements into his own martial arts and fitness practices. When he decided to pursue a Master’s degree in psychology at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York in the early 70s, Haltom found a surprising number of students who were drawn to his multi-dimensional approach to music, dance and martial arts. He taught his first Tai Chi class in the summer of 1973 with one student, but by the next year the class ballooned to 70. By 1982 Haltom found himself opening the Aquarian School of Movement Therapy; four years later the center moved to another Ithaca location and became the Agape Institute for Movement Studies, offering a full range of classes in African drum and dance, Tai Chi, Kung Fu and yoga.

Haltom developed new techniques and practices that were based on the idea that “you could be rhythmic and continuous, and that could still be a basis for a kind of strength and power.” He envisioned the both the Aquarian School and the Agape Institute as embracing a “multi-cultural approach to becoming more mindful and more conscious of the body.” One of his most compelling classes, which he calls “Atlantean Yoga,” combined the fundamental postures of Indian Hatha yoga with circular motions of African dance.

Haltom was surprised at the growth of his organization and the general interest in his teachings.

“I never really thought that I was evolving something, but by about 1982, I was pretty aware that there was something going on here between Africa and China – and India, with the yoga postures,” Haltom explained, as he described the basis of his new form of yoga. “Atlantean Yoga involves the idea of taking postures which appear to be still, but because you’re breathing there is an opportunity of engaging in small, spinal flexing movements. You can find ways to keep the posture intact but at the same time undulate the spine and thighs.”

Haltom says that his work with the intensified breathing and movement innovations of Atlantean Yoga develops a particularly powerful sensitivity and connection to the Life Force, and presaged some of trends that would occur with the widespread popularization of yoga in the 90s. In particular, the practice of “Power Yoga," a form of athletic yoga with enhanced cardio-vascular activity developed by Rodney Yee in California, and Sanyasin Yoga, are both similar to Haltom’s Atlantean Yoga system.

During the time that he was developing the Aquarian Center and the Agape Institute, Haltom also studied with Chinese martial arts master Mantak Chia in New York City. He found that Chia’s teachings on the Chinese philosophy of Taoism and its body systems were applicable to almost all aspects of his personal life, right down to his African drumming technique and the way he played salsa music. Haltom developed a close relationship with Chia, and after a few years Chia invited him to work more directly in transmitting Chia’s knowledge to a wider range of students. It was a difficult decision, as master Chia was becoming a world-renowned teacher and his work eventually resulted in new interest in Qigong – Chinese esoteric yoga and healing techniques – in the United States and the Western world.

“Mantak Chia invited me to join him in the process of taking his teaching forward to a new level. And I really had to think about it, because I knew that in the back of my head there were other things that I didn’t really understand or know, and I turned him down,” Haltom explained. “It was very strange because I was getting a lot from his teachings, but I declined because of this inner feeling that I could see all of these connections between Africa, China and India (in my own work). That was the vision in the back of my head and so I declined, and that was hard.”

Haltom believes that African traditions and practices are generally not appreciated for their potential contribution to health and healing because they involve a mind-body orientation that is very different from standard Western thinking. But developing these practices are well worth the effort, because they can lead one to a new awareness of inner knowledge and the “collective unconscious” that is not accessible through conventional education.

“I call it from the bottom-up, because you learning and thinking and cognizing from a different part of your whole being, which I think is part of the collective unconscious anyway,” Haltom explains. “I think we all have this going on inside of us – it’s just about getting different ways to stimulate and open doors so this knowledge can come out.”

Haltom currently teaches a few classes per week at the Cayuga Wellness Center, but his life has been somewhat redefined by his psychotherapy work with Cornell students and in his own private practice. Although he does less mind-body activity, Haltom still feels his work as a psychotherapist parallels his involvement in music, African drumming and the martial arts and is similar to the traditional role of a shaman.

“Even right now, as a psychotherapist in a place as diverse as Cornell, I would see myself not so much as a psychotherapist as a shaman,” Haltom points out. “I say that because what I’m doing is assisting people to come in touch with a deeper part of themselves. We all have housed in us a relationship with the Life Force that is in each of us and in all life.”

Beyond the wealth of awareness and inner knowledge that can be developed through African music, movement and dance, Haltom believes Africa has a more general “gift” for humanity through the cultural processes that are reflected in jazz music and improvisation. Much like he adapted Tai Chi, Kung Fu, yoga and music to his own inner themes of rhythm and movement, Haltom sees a powerful adaptive intuitive consciousness that is inherent in African culture. Haltom believes it “takes a lot of training” to develop this consciousness, but the effort leads to “the opportunity you might have to start living a life like that.”

“I think that Africa comes with a unique plan for adapting right now, in the current moment – and to each and every moment – in a very spontaneous and fluid fashion,” Haltom says. “Each and every moment in life is a mystery, and the mystery is solved when I come to the mystery myself, connected to my inner lawfulness, and I can relinquish control and give over to this trust of there is something within myself that can adjust perfectly and adequately to a certain moment.”

Truly well spoken, like a griot, a fundi, an African sage. Through jazz, drumming, martial arts and more, Haltom has shown us that there are many inner gems of African mind-body wisdom, and many pathways to the Motherland in the heart.