...

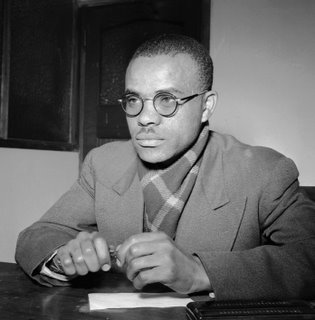

The first column of the Eye on Africa series is this interview I did with Hugh Masekela just before he played a Fourth of July concert at Five Points here in Denver. He was very open and easy going, which I found rather surprising for an artist of his stature. A lot of times famous musicians can be full of themselves, emotional, moody, etc. After we sat down I put my cell phone on my lap and Hugh immediately warned me about the cancer radiation radiation threat to my family jewels! Funny guy ... Hugh's autobiography, Still Grazing, is absolutely fabulous--once you pick it up, I guarantee you won't be able to put it down. The man blazed a trail from bebop to rock, soul, and all kinds of African genres, and he opened a lot of people's eyes to South African music. He organized the music festival for the "Rumble in the Jungle" Ali vs. Foreman fight in Zaire, the first international Black music festival in Africa. Now that's history...

Hugh Masekela On Music and Politics

Master musician, jazz artist, activist, storyteller and spokesman, Hugh Masekela’s spirit has burned bright through four decades of tumultuous world change. The young boy who mastered his trumpet on the dusty streets of South Africa’s townships was destined to use his instrument as the sound of freedom, yearning and triumph, the sound of dissonant harmonies and fantastic grooves that naturally brought everyone to their feet.

Going into exile in the 60s, moving from Britain to the United States and throughout many nations in Africa, Hugh always used his stage as a platform to denounce apartheid while simultaneously collaborating with and learning from some of the world’s greatest artists, including Fela Kuti, Bob Marley, Miriam Makeba, Herbie Hancock, Dave Gruisin, Chick Corea, Donald Byrd, Ron Carter, Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis and many others. As a witness to the American civil right movement, the winds of independence in Africa, and finally the fall of apartheid, Hugh’s music and storytelling chronicles the modern awakening of Africa and her people. Whether it’s the irrepressible joy of his 1968 mega hit “Grazing in the Grass,” or the gutsy power and pain of “Stimela,” or the mystical transcendence of “Marketplace,” Hugh helped bring African music—and South African music in particular—to the mainstream of global pop culture.

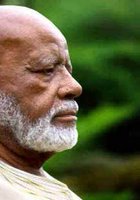

On Independence Day—that most American of holidays—Hugh brought his magic to the streets of Five Points for the annual “Jazzy Fourth” event. Well into his sixties, Hugh’s trumpet and his raspy, melodic, chanting voice still rocks the stage with a feeling of timelessness and eternal youth. With the crowd there was no doubt. Black, White, Hispanic, young and old, jazz lovers, hip hop kids and summer revelers were all carried away by the euphoria of Hugh's impeccable performance. In the midst of the new challenges of rebuilding South Africa and pursuing a multitude of music, film and writing projects, Hugh has mellowed and wizened, seeking new ways to express his artistic vision and philosophy. Before the performance I had the chance to sit down with him at the Gardenia Hotel, where he pondered his journey through the modern history and the music industry. In his unassuming way, Hugh seems like an elder cultural statesman of Africa, a modern day griot overflowing with stories, thoughts and ideas that are much more than what one might expect from most musicians. Relaxed, yet full of energy, Hugh seems ready to share the depth of his spirit as if it was as natural as channeling the air through his trumpet.

JA: How has your music changed since you returned to South Africa from in the early 1990s?

HM: It hasn’t change much—South Africa hasn’t changed that much. Our political situation has changed, but the damage that was done by apartheid hasn’t changed very much. If it took 50 years to build apartheid, I think it will take 50 years to get rid of the damage done (by apartheid). It will probably take two generations. Our biggest dilemma in SA is that we are a liberated people who are poor. The people who are really free people are our oppressors. We made a deal that was very much to their favor. They were pariahs internationally, they couldn’t do business anywhere and everywhere they went they were afraid to say they were South Africans. Now everywhere they go they get applauded for being South Africans and they have all the new opportunities. If you look at all the new international South African businesses, they are basically White businesses, or they are businesses that are owned by people who have been co-opted by the old South African economic establishment—just like many of civil rights leaders in the States. What happens in most liberation struggles is that people don’t remain militant—they don’t remain vigilant and guard the freedoms that they’ve won. And instead they get manipulated into being co-opted into the establishment—especially by the old financial establishment—and it’s a danger we’re facing right now. In South Africa right now close to 50 percent of the population is impoverished, and those are the people worked the hardest and suffered the most under apartheid. I am now into writing a second novel—I wrote my biography, “Still Grazing”—but in my novels these issues come up a lot. I’m also going into film, to create real life characters, portraits and profiles of what’s really happening right now in South Africa. We’re not being harassed by the police—if you have the means and the education, you can live very well—but it is the underclass that are suffering. And all the non-governmental solidarity organizations that were supporting us during apartheid have said “Hey, you’re free now. We’re going to help other people.” So from a solidarity perspective we don’t have any friends but the documents that freed us. That’s the reality in my head of the new South Africa.

JA: What do you think is the answer?

HM: A wonderful thing about our current president is that he realizes that South Africa’s freedom is meaningless, unless the rest of the international African community is free—unless all of us, the so-called Diaspora can be free. We all won political freedom, but we need to win economic freedom. But that is not going to come through protests and soapboxes--it is a thing that is going to come through synergy. I think the answer is cultural synergy. To achieve that cultural synergy we have to come out of that denial against us all being Africans that we are manipulated into by colonialism and oppression. We’re the last consumer community, all over the world. We are discouraged from seeing each other as one unit. Once we can do that—the answer to that is our cultural background, our historical glory—when you look at people of African origin from all over the world, you think that our existence started with slavery, or colonialism. But we were there long before. And that is the veil that is put in front of us. I think if we can remove that veil and see who we really are, and where we come from, and that we really did civilize the world, maybe we will wake up and say, “Hey, let us get together and produce…” At home (in South Africa) I’m involved in recording, television and film companies to build an entertainment infrastructure that is home-grown and home-owned, African-owned, that will replace or transform the present European ownership with our own vision and our own design. And then maybe we can source from our traditional customs and the glory of our heritage—that is the future thing we can sell to the world. I think that’s what makes the Indians who they are, the Chinese who they are, the Japanese who they are, even the Americans who have a hybrid culture—there is no culture that has been sold better than theirs.

JA: In SA there’s a lot of talk about the idea of an “African Renaissance,” but in the United States, we don’t hear any talk of an African Renaissance. Can you elaborate on that?

HM: Well, talk is not sustainable, but action is. It’s another thing that Thabo Mbeki, our president put out there, hoping people would pick up the torch and run with it. But renaissance cannot come about through thought--it has to be acted on. The only way we can act on it is to come out of denial about who we are as Africans. Because as long as we deny who we really are, what our historical heritage is, there can’t be a renaissance, because renaissance is going back to your roots. Celebrating and glorifying your origins—I think that’s what the Indians and the Europeans and the Arabs and the Jews everybody else is doing. We’re the only people who are not doing it. If you look at other people in the world, they have seasons, and sometimes they have whole months that they celebrate something about who they are. The Christians get us from November to January. But we African people, we don’t have one binding celebration that we can say that we can say “this is our day” internationally.

JA: Do you see Kwaanza as fulfilling that role?

HM: It’s one day, and it’s sort of an alternative to Christmas. I don’t think we should be involved in alternatives to other cultural celebrations. I think we should come up with our own. And we have our own—if we look back at history—if we look back at the empires we had, like the Songai Republic, the Monomotapa Republic and so on. We invented the wheel, we invented math, we invented geometry—we have so many resources to celebrate. But we have to accept that we are those people, and we have to cancel the history of our conquerors, and say this is really who we are. We can go to the schools of our conquerors, but just like the Jews have like Friday and Saturday, the Muslims have every Friday they get together and the Christians have Sunday and then the Buddhists have their days, we must have our own days. Those things are historical, and we’re going to have to research.

JA: Can you tell us a little about your new album Revival, and how it relates to some of these issues?

HM: On my new album and I have song called “Woman of the Sun” I talk about a woman who is proud to be herself, proud of her African beauty. On track number 9 (“Ibala Lam”) talks about how we should be proud of the dark skin we’re in. Track number 10 (“Sleep”) I talk about sleep… How do we sleep at night, when people are exploding in the minefields in Angola and other places because of surrogate wars? How do we sleep in Rwanda with the smell of all those bodies all around us? How do we sleep Nigeria, the Ivory Coast, in Haiti, when there are people who are working against us but are part of us, people who are surrogates for foreign industrial interests? All the wars in Africa have nothing to do with personalities or African issues. It’s all about the fact that there are resources there. The international industrial interests are manipulating our leaderships---and if those leaderships are not satisfactory they are ousted, and they put in a leadership that will protect the exploitation of the raw materials of that area.

JA: I’m particularly fascinated by “Ibala Lam.”

HM: That song is an adaptation. I actually first heard it in 1979 from a young man named Lebo M (who eventually went on to write and produce the multi-platinum soundtrack for Disney’s “The Lion King”) who was only 14 years old, and he had just arrived out of exile from Lesotho. He was brought by Tim Tahane who was at the World Bank, and he also brought another young guy named Vernon Molefe, the younger brother of Phil Molephe from SABC Africa. Tim called me and said, “Listen here, I’ve got two boys I brought from Lesotho. I want to send them to school, but they tell me they are musicians, so I want you to listen to them and tell me if it’s worth my while to hassle for them to get into music school.” This little guy started singing this some “Ibala Lam” and it brought tears to my eyes. I never forgot it from that day. It says, “this color of mine that is so Black, I’m proud if it—it’s my shining armor.” Most of my recent hits in South Africa are have been old songs, songs like “Tainia” is an old Xhosa wedding song, it’s more than two centuries old, and “Mamuri:” an old Tswana song.

JA: Why have your South African hits been old songs?

HM: Because I’ve been on a revival quest. I’m trying to show that our past, is our wealth. That which was removed and denigrated and vilified by our conquerors as being barbaric and backward—that is our finest self. Whenever I bring that forward it becomes a hit, because people feel it right away. It’s like “Yea, this is about me.” The young people think that it’s new. But it’s in their genes—they feel it in their soul. There’s problem with that here in the States with Black people—the removal of the melody. Today there’s hardly any song you can sing along with. What is sponsored is mostly anti-education, it’s anti-respect, it’s about showing booty, it’s just beats and grooves and rhythm but there’s no songs. What we don’t realize is the magnificence of international urban recreation, came from African Americans. The whole world tries to walk like you, talk like you, to dance like you, to sing like you, to dress like you, but they won’t tell you that. But you can see it happening all over. That’s what brought me to the States—I felt that. And all that, I watch killed. I watch jazz killed—the closing of the clubs (that thrived) when I first came here in the 60s—Birdland and the Blue Note all closed down, and that whole jazz movement closed down, because people who came out of Bebop could think and they had opinions and they were not afraid of White people. Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie Monk and Mingus, they were not liked by the White establishment, because they came up with something that was magnificent and new and they also thought. Duke Ellington was invincible; he and Billy Strayhorn were major intellectuals. Had they been White people they would have been placed far above George Gershwin and Cole Porter. They were prolific. But what spoils things now is the non-melodic. Even the dances—there’s no dance where you can say “that’s the funky chicken”, or “that’s the dog,” or “that’s the slide” or “that’s the twist.” When I came here, those were tangible dances. People say I’m socially paranoid, but I know there is a deliberate and ongoing campaign to make sure that the excellence of international African magnificence is curtailed. That’s why Bob Marley was done in, that’s why Miriam Makeba was blackballed out of here, that’s why Belafonte sort of disappeared, that’s what happened to Sly and Jimi Hendrix. James Brown was a major survivor. People think that that campaign is over, but that campaign doesn’t go away.

JA: How do you see this in relation to South African jazz and the tradition you came out of?

HM: The thing that is bringing (music) home, is that the young (South African) men and women are technologically very advanced. They are building their own studies and production companies, and that’s what we’re involved in with Chissa (Hugh’s record label). I think that slowly we are getting into an era where we’ll do our manufacturing, our own distribution and our own marketing and sales. And hopefully soon we’ll have our own radio stations and television stations and film companies and we’ll come up with a new thing. With the help of security companies we’ll be able to come up with a whole new entertainment infrastructure. Everything has to be continental. The continent has to be safe for Africans to have a good time. Africans need to have a good time—Africans haven’t had a good time for centuries, and we have to build that. But I don’t think it’s in the mind of most African governments to do that. South African jazz is a media myth in growth. Basically there is no African entertainment industry—if it exists its very miniscule, it’s nowhere near the Japanese or the Chinese or the Europeans or the Indians, and it has to go there, before we can say South African or African music is happening. Of course there’s few artists, but right now it’s not happening. It has to be built.

JA: When I was in South Africa, I heard a lot of complaints that younger South Africans were losing interest in their culture because of their interest in rap and African American music and television. Do you see any evidence of that?

HM: If anything the youth in South Africa are the only ones who are looking up. People like Don Laka, people like Mzwai Bala, who produced my last album and was the leader of TKZ, people like Oscar Mhlangwa and Bruce from Brothers of Peace who produced Bongo Maffin, Malaika and Mafikizolo, that was all native languages. These are all young people, but they are really aggressive about their origins, their past and their heritage. They are the people who are forging an African renaissance, and those are the people I’ve been working with. I find that their curiosity for the past is insatiable. I think they are the hope. I think the adults have lost it. I think that in the whole international African world, adults are the ones to blame, because they left their children to the television, and they bought their own television and closed themselves in their own rooms to watch their own programs and their agendas are to be as Western as possible. And they’re not teaching their children. I know my grandchildren are going to be fine, because my children are fine. But I think that the international African adult has abandoned their responsibility to keep their family values going and to point their children in the right direction.

JA: Was there ever a time when you thought you would never see the defeat of apartheid in your lifetime?

HM: I never thought that I would go back home—I never thought that South Africa would be free in my lifetime. But I knew it was going to be free one day. I not only thought I was going to die in exile, I was sure of it. Especially after I went to live in Botswana between 1981 and 1985. I said to myself, “This is the closest I’m going to be to home.” I was able to organize a music school, my record company built a studio, and Gabarone started to become a cultural hub of Southern Africa, and the death squads came and so I went into second exile. I’ll never forget June 17, 1985, when I left, I thought, “Here I am going back into second exile.” But I didn’t feel badly for myself, because I knew that I would survive. I felt bad for the people of South Africa, and Africa, because I knew that to a great extent Africa would never be free until South Africa was free. But now that South Africa is free, that’s only step one. The next step is to free Africa from surrogate wars that are waged on behalf of international industrial and economic interests. And then we have to get rid of the frontiers--the borders—because we didn’t put them there. That won’t happen in our lifetime, but it’s very important to be part of that initiative. JA: Your first major hit in the US, “Grazing in the Grass” has become something of an American classic, although a lot of people probably know the tune, they may not know the artist. Almost 40 years have passed now since that powerful time when you wrote “Grazing in the Grass.” Can you tell us something about how you feel when you play that song now, and the feeling and the atmosphere of the time you wrote it? HM: It was written by a friend of mine Philemon Ho. He came to New York with a show called Siponono. He was with Caiphus Semenya and Letta Mbulu and Jonas Gwangwa. It’s great to have songs from South Africa like “Grazing in the Grass” and songs like “Pata Pata” and grooves like Ladysmith Black Mamabazo’s “Homeless.” It’s great to know that the music of the people you come from has a universal effect. I think that is what helped free us, because we were able to reach the whole world, and the whole world came to our side and said, “These people are something else! We can’t let them be oppressed. We need them to groove!” After Paul Simon did Graceland, every artist couldn’t do an album without an anti-apartheid or free Nelson Mandela song. So there’s something about South African music that is universal that hits the whole world. People embrace that music also because of our liberation struggle. But now we’re building a phase where people have to like us just because our music is good. I think the staying power of a song like “Grazing in the Grass”—which has been a hit for 3 different groups, and a number one hit for two of them—shows we’re going to have something that in future will touch the world in a much bigger way, because our way is clear now. It gives me great hope for the future.

To find out more about Hugh Masekela and his new Revival album, visit: http://www.headsup.com/ecards/3093/i-3093.asp Also visit: http://www.music.org.za/artist.asp?id=96