Africa's Environment and a Woman's Mission

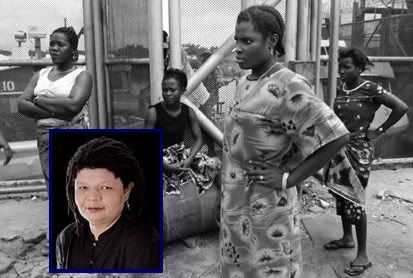

A group of Nigerian women protesting environmental hazards at on oil refinery in the Niger Delta. Insert: Africa environmental justice activist Leslie Fields.

Before I interviewed Leslie Fields and talked in depth with her, I had given some thought to ecological issues in Africa, but I didn't see them as clearly as I do now or with the same sense of urgency. I knew something about the problems in the Niger Delta as well as climate change, soil erosion and desertification, but Leslie gave them a new prescience and a new realness. One thing I didn't mention in this article - although Leslie hinted at it - is the effect global warming is having on flooding, as the snows of Kilimanjaro and nearby mountains are melting. It's not as big as a problem as desertification, but it fits in the whole environmental-ecological picture in Africa. As more African Americans - and more people in general - travel to and become interested of Africa, we also have give consideration to these issues and become more involved in environmental justice.

Africa's Environment and a Woman's Mission

Leslie Fields is an African American woman who battles for sanity and reason in an insane, unbalanced world. Her long dred locks, high cheekbones and welcoming smile project soft-spoken character and a deep bond with the African Motherland she works so hard to protect. At first glance, one might not expect that this non-assuming woman is an international attorney who takes on the likes of Shell Oil and powerful government interests on behalf of unknown, powerless people. Yet throughout her career, Fields has found herself tirelessly admonishing, cajoling, exhorting and otherwise influencing an extraordinary array of ambassadors, cabinet ministers, senators and congressmen, CEOs, community leaders and Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) on environmental issues.

Most people think that ecology and environmental activism are the purview of liberal, touchy-feely Whites who live in suburbs and wear Birkenstock sandals. While there appears to be a lack of African-American interest in environmental activism, Fields encourages people to look beyond surface appearances and see that many ecological issues have important racial implications.

As an idealistic law student at Georgetown in mid-80s, Fields never studied environmental law, nor did she see herself becoming involved in the field. But during her early years as a practicing attorney working for the Texas Legislative Council and volunteering for the Sierra Club and the NAACP, she began to discern trademark patterns of community exploitation by large energy corporations.

“I got started doing environmental justice work here, in the United States. I realized very quickly all these companies were doing the same kind of exploitation – whether it’s “Cancer Alley” in Louisiana, or the “Chemical Corridor” between Baton Rouge and New Orleans,” Fields explains. “You can’t live down there and not notice this. It’s very obvious; all these chemical companies and petrochemical companies are all sited in Black and Latino low-income neighborhoods.”

Through her legal role with the Texas Legislative Council, Fields drafted the first Texas Birth Defects Registry. At the time, many babies with birth defects were “being born in clusters” of locations near polluting plants, factories and chemical refineries. The Birth Defects Registry helped disseminate information from county hospitals so the problem could be viewed from a wider perspective. Her work on the Birth Defects Registry sparked off a new interest and lifelong passion for understanding the specific impacts of environmental policies on families and communities.

Fields adventurous backpacking trips and various travels through Mexico, Central America and South America only confirmed the same problems she saw in Texas and Louisiana. As she became more aware of the broader scope of environmental issues, Fields began meeting and networking with people from the countries she traveled in.

“As I traveled, I saw how the same companies were contaminating the same kinds of neighborhoods in Mexico and Central America,” Fields said. “Then I went to Ecuador for the first time, and I went to the Esmeraldas area, which is all Black, and that’s where they have their oil. And again, the same oil companies and their subsidiaries were contaminating that area.”

Fields new contacts would lead to involvement with larger groups such as the Indigenous Environmental Network and the National Black Environmental Justice Network, an organization she helped found. Fields gets excited when she talks about the friendships and sense of community she developed through her environmental justice work. She feels environmental justice is unique because anyone with an interest can get involved – from scientists, lawyers and students to grandmothers, church members or community leaders.

“My favorite people are older women, kitchen table advocates who see a problem, with no funding, no big organization behind them, and they get themselves together and they take on the city council or they take on whomever,” Fields said, laughing as she describes the culinary joys of her regional “Interstate 10” diet. “They’re involved in everything, they’re the keepers of the neighborhood and they also feed you. They give you bread pudding and sweet potato pie and barbeque and you drink beer and it’s just wonderful. People still sit around on their front porch and drink iced tea or beer and you see plant in the background with the flair and that’s where everybody has to work.”

Fields believes that everything she has done locally in the United States “translates globally” and naturally fits into the same patterns and environmental justice trends worldwide. At the World Conference Against Racism in Durban, South Africa in 2001, Fields and other activists worked hard to write platforms and draft position papers to elevate environmental justice issues to same level of other human rights issues like human trafficking, racial and sexual discrimination and torture. In Durban Fields met Niger Delta and Angolan activists who would help her focus on some of the most pressing environmental problems in Africa. After the Conference Fields became the director of the Friends of the Earth’s Global Sustainability Initiative, and then returned to South Africa to participate in the World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg in 2002. Her work with Friends of the Earth – one of the world’s largest environmental organizations – initiated a new phase of work on African environmental causes.

With the highly visible martyrdom of Ken Saro-Wiwa in 1995, the international media was gradually becoming aware of the exploitation of the Ogoni people and other ethnic groups in the Niger Delta region through the actions of multinational oil companies like Shell, BP and Agif. As Fields traveled to Nigeria and worked with NGOs and government officials she became sensitive to many of the complexities of Nigeria’s economic growth and development. She feels very strongly that the problems in the Niger Delta are one of the world’s worst – and least followed or understood – environmental crises.

“The Niger Delta is a civil war that no one is paying attention to. Everybody hears about Iraq, everybody hears about different places in the world like Palestine, but this is a civil war, and people are suffering and dying, people are being contaminated, and women are having miscarriages,” Fields explained with sadness and anger in her voice, adding that many problems are accentuated by poor oversight and lack of environmental regulations and standards. “Nigeria flares and wastes more gas than any (other) place in the world because BP and Shell and Agip just care about getting the oil – they don’t care about what happens to the gas getting burned off in the production process.

“They flare it on the ground, they flare it ceiling high, they flare it all over the place. So all these communities have terrible pollution. I’ve seen pipelines next to health clinics and elementary schools – they just put them everywhere.”

The situation in the Niger Delta is part of a bigger problem with other countries in Africa like Angola and Equatorial Guinea. Fields describes these places as being “awash in all these new oil wells, and people are living in filth.” These problems have new implications for African Americans, as volatile global conditions are forcing the United States to get one-quarter of its oil and gas from West Africa. In the drive to satisfy its thirst for oil, the American government and US foreign policy will “follow the same model” of Shell and BP, creating conditions that oppress the lives of Africans.

Fields is adamant about raising these issues in African-American organizations and forums like the Association of Blacks in Energy, the NAACP and the Congressional Black Caucus, where often she is the lone environmental justice advocate. She feels too many Blacks do not see the multi-layered connections between America and Africa.

“As African Americans, we cannot walk around now with our newfound knowledge and our Akente cloth and pretend like nothing’s happening over there. People are dying so we can drive SUVs,” Fields says passionately, adding that environmental hazards have created a cholera epidemic in Angola. “In the Niger Delta and in Angola people live in the most appalling filth so that oil companies can get that oil out of there and sell it to us at a price that we can live with. We can’t pretend that we’re buying African art and everything’s ‘brothers and sisters’ over there and we’re part of the problem because of our consumption patterns.”

Fields says she has had some success and positive response from the American Association for Blacks in Energy – an organization of African Americans in executive positions in energy industries – and the Congressional Black Caucus. During Congressional Black Caucus week in Washington, D.C., a great deal of networking occurs between Black Congressional Staff, the Energy Department, energy professionals and Ambassadors and diplomats from African countries. Fields says she has met the Ambassador from Angola, Madam Ferreira, who has said she would love to get support for renewable sources of energy in Angola, but her country needs direct foreign investment to build basic infrastructure damaged from their 30-year civil war.

Beyond environmental and economic issues related to the oil industry, Fields is even more passionate about her work combating the problems of climate change and global warming. She describes ecological issues as the “back-story” to many of the conflicts occurring in Africa, and she feels more people need to understand climate change in the context of soil erosion, desertification and the effects it has on African populations.

“Climate change creates more conflict and migration than anything. People migrate because of floods and famines and because of desertification,” Fields says emphatically, her voice rising in indignation. “Remember those floods in Mozambique a few years ago? And the situation in Darfur is the way it is because women have to go out and find water and get fuel because there isn’t any anymore because of desertification and climate change, and then they get attacked by the Janjaweed.

“Climate change is fueling migration and making people move to areas where other people don’t want them. And it’s all about water, and it’s all about energy.”

While these global challenges appear daunting, Fields is enthusiastic because activists are making breakthroughs by applying pressure through critical avenues in the corporate world. Ironically, Fields points out that these new movements are being driven by some of the same activists who organized the movement to stop American universities from investing in apartheid South Africa. Along with Sister Pat Daley, one of the progenitors of the divestment movement, Fields served on the board of the Coalition for Environmentally Responsible Economies (CERES), an organization that encourages large pension funds, insurance agencies, banks and institutional investors to vote for shareholder resolutions that reflect the true costs of “climate risk.”

Climate risk may include damage costs related to floods and hurricanes such as Katrina, which devastated the Gulf Coast last year, or any costs associated with the ecological impacts from climate change. Fields did similar work through Friends of the Earth by advocating that international financial institutions such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, as well as the US Export Import Bank and the Overseas Private Investment Corporation carefully monitor costs associated with oil companies investing in the Niger Delta and Angola. Fields lobbied for more stringent requirements and standards regarding political risk insurance, making it more difficult for oil companies to write-off losses associated with business activities in regions known for poor environmental regulations and oppression.

Fields is very proud of the work she and other women activists are doing in Africa. She says one of her highlights in Africa was meeting Wangari Maathai - the first African woman to win the Nobel Peace Prize - at the World Conference Against Racism in 2001. Dr. Maathi founded the Greenbelt Movement in Kenya, which has planted 30 million trees to stop soil erosion and desertification while also enhancing Kenya’s development position via the Kyoto Protocol on Climate Change.

“Women are holding up half the sky there – they’re doing it. I’ve met all kinds of women ministers and parliamentarians and women who are running NGOs, and women who’ve been through a lot,” Fields says. “Wangari Maathai is the best example of what I’m talking about. She went through a lot – she was imprisoned and beaten. Ellen Johnson- Sirleaf (the new president of Liberia) was also incarcerated.”

Fields feels blessed to have the opportunity to work in Africa, and she feels hopeful that growing numbers of African Americans will continue to travel and work in Africa.

“I definitely feel connected (to Africa), in a very, very broad sense, whereas growing up, we didn’t have that. Now I know more Africans, I know people from Africa who have friends here, and it’s enriched my life in a lot of ways that I can’t even put words to,” Fields says, with a sense of gratitude. “I search things out, and if something has an African Diaspora angle to it I will gravitate toward that. I’m much more of a critical thinker as an American because I have this Diaspora feeling in me. I try to think how my life will affect other people, particularly Black people.

“Because if we don’t do it, nobody’s going to do it.”